By Michael Stepniak

Where do people live in Detroit? Where does investment go, and for what?

Revitalization (and its cousins: Revive, Restore, Reinvigorate, and so on), is more than a buzzword in Detroit. It is a culture of memories. It is a romance with a once-prosperous city and its decay. Consider the word “revitalization.” It descends from the Latin re for “again, back, anew, and against,” and vitalitas, for “things pertaining to life.” Combining this last definition of re with vitalitas presents the most accurate definition of revitalization culture in Detroit. A romance with the past and a focus on its return is against the things that pertain to life in the present and future city.

Visually, at the height of its postwar wealth, Detroit was grand. The majesty of its industrial works and its Art Deco skyscrapers is undeniable. The vast, sprawling places in which working class people achieved home ownership, the places in which the middle class grew: these cannot be ignored. The city’s rapid development, industrialization and population explosion, and the physical spaces that were created represent a remarkable period in the city’s history.

The narrative of revitalization employs specific rhetoric: Visions of “former grandeur,” “former prosperity,” and a “return” to these things are embedded in the collective imagination of local politics, development and culture. The motto on the city’s flag is Speramus Meliora, Resurget Cineribus: it will rise from the ashes, we hope for better things. These words were spoken by Father Gabriel Richard, a French priest and local politician after the fire of 1805 burned the city to the ground (Herron 669). Richard’s words have found new life in the local popular vocabulary.1

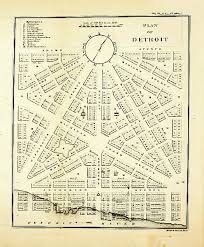

Woodward’s Plan

What is the geography of revitalization culture in Detroit? Generally speaking, it is an area of approximately 7.2 square miles, known as “downtown,” “greater downtown,” and more recently, “The 7.2” (7.2 SQ MI). This geographic understanding of Detroit also traces back to the 1805 fire. In 1806, judge Augustus Woodward designed a new city, based on Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s plan for Washington, D.C. (Moore 120). Much of Woodward’s plan was discarded, but it was largely adopted within the one square mile city core. A century after Woodward, the rapidly growing metropolis adopted a City Beautiful plan, and greater downtown became a place of French-style architecture, wide boulevards and green spaces (Bluestone 246). This is the physical geography that revitalization visits with its rhetoric.

How does revitalization culture effect planning? Two centuries after Woodward, planning language and aims have not adapted to the new realities of a changing Detroit. Planners and city-saving developers operate under the premise that Detroit has a core, and that it is Woodward’s downtown. The reality is that Detroit proper is 138 square miles, and nearly its entire population resides outside of the 7.2. An additional layer is that Detroit is now a metropolis: 3.6 million of the metro area’s 4.3 million residents live outside of the city limits. Woodward’s core is the city center in imagination only. Language commonly used by residents is telling: every outside of greater downtown is known as “the neighborhoods.”

Detroit Future City (DFC) is the latest plan, the de facto master plan. Unlike many previous plans, it attempts to acknowledge the people and the existing city. DFC does engage with communities and structures, but it does not confront them. It cannot get away from its mission of revitalization. The document begins with the prosperous industrial postwar city, skips to the mess it is today, and moves forward towards revival, allocating the bulk of initiatives, and therefore funding, to the greater downtown area. One stark example of its non-confrontational tone is that in 761 pages, the word “racism” is not used once, but the word “revitalization” appears dozens of times.

It is impossible to have a serious discussion about Detroit, its past, present or future, without discussing race and racism. It is one of the things that has shaped the city’s spaces and continues to do so. Racism is one of the most important problems facing any person, group or government who hopes to re-plan the city.

DFC also fails spatially. DFC held many community meetings during the process of crafting the plan and its presentation to the public. Yet in one meeting in 2013 a DFC representative stated that the plan for the neighborhoods near 8 Mile Road and Gratiot Avenue was to “let them lie fallow.” DFC is proposing almost no investment for the outermost neighborhoods. This, despite that these neighborhoods are among the city’s most densely populated.

Revitalization culture is a romantic view of Detroit in the mid-20th century: a city of 2 million people, giant factories, prosperous workers, beautiful parks and wide boulevards, personified by legends from Augustus Woodward to Henry Ford. It lives up to its motto and has risen from the ashes. This view idealizes a period that was far from ideal. Two world wars, the Great Depression, the 1943 race rebellion, red-lining, union battles and riots such as the Ford Massacre and the Battle of the Overpass, systematic union discrimination against black workers: all this and more took place during this time in the city’s history.2 This is nostalgia expressed as a narrative that drives development within a small geography that is no longer central in a meaningful way to a large proportion of the population.

White racism against blacks by individuals, governments, unions, banks and systems has been well documented as a destructive force in Detroit, as have automation, globalization, and government-subsidized suburban development.3 Nostalgia refuses to confront these issues. It selectively ignores the Detroit that came before the industrial city. Post-European Detroit has three centuries of history under the rule of three countries. As a region, it has been inhabited for 8,000 years (Roberts 252). There have been many incarnations of this place, from the Mississippians to the Mississauga, to the French, British and Americans. No doubt there will be many more.4

The development crowd asks “how can we revitalize Detroit?” and answers its question as follows: “By restoring its former grandeur, with a focus on the historic city center, which is our best chance to rebuild a tax base” (Neavling). There must be an opposing question that rejects the assumptions of centrality in downtown and focuses on the places where people live.

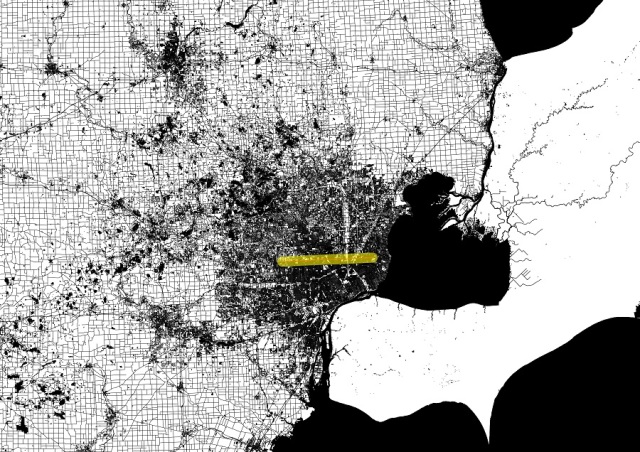

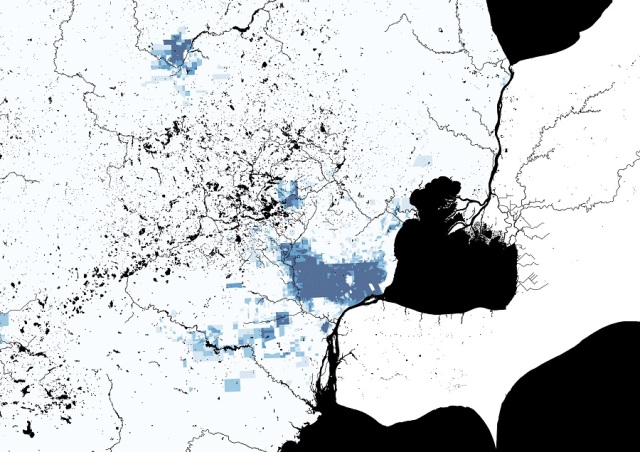

Figure 1: Infrastructure in Metro Detroit

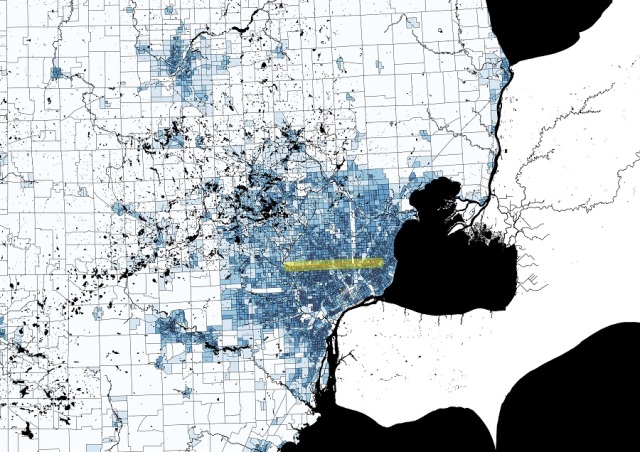

Figure 2: Population Density in Metro Detroit, 2013.

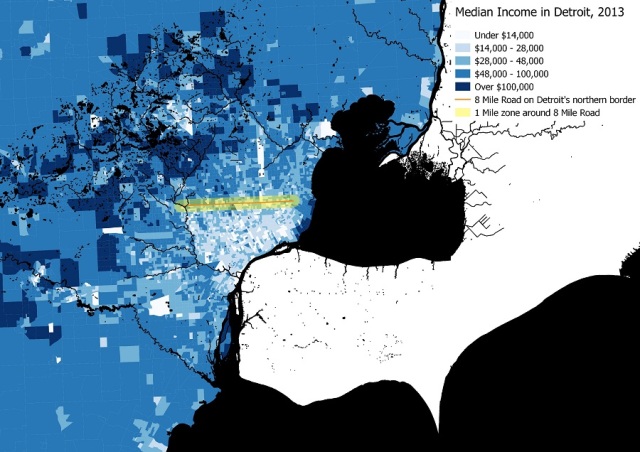

At the heart of metropolitan Detroit is 8 Mile Road, a 20 mile long border between the city proper and the northern suburbs (figs.1 & 2). It is the line of demarcation between counties, cities, and school districts. It is a racial, economic and cultural barrier. Stark divisions of race and class exist between the city and the suburbs (figs 3 & 4). 8 Mile Road is the center of the metropolitan areas population, its geography and its conflicts.

Figure 3: Racial Segregation in Metro Detroit, 2013. Darkest Blue: >75% African American, Lightest Blue: <14% African American. African Americans are 14% of Michigan’s population.

Figure 4: Class Segregation in Metro Detroit, 2013.

The border kills democracy, or so it appears. The road itself is not divisive, it is an immense piece of infrastructure and must be seen on those terms as well, while acknowledging its racial, cultural and economic contexts.

“Restoring Detroit” is not an idea that implies evolution. A focus on postwar prosperity does not situate the present, the future, or even the formerly prosperous Detroit within its multiple histories. Postwar Detroit, Woodward’s Detroit, majestic as it was, must be thought of within the context of its racism, its deeper past and the way in which these things are still spatialized.

In Augustus Woodward’s day, what is now downtown was the entire city. Today, metropolitan Detroit covers all or parts of five counties, spanning thousands of square miles. The ideal that has been cemented into revitalization culture ignores that downtown is no longer the center. For the three million residents of the northern suburbs, and a good portion of the 700,000 residents of the city proper, 8 Mile Road is the true center of the region.

_________________________________________________________________

Notes

1. Examples of “rising from the ashes” rhetoric do not only apply to revitalization, but to recovery from disaster. See Reclaim Detroit’s home base destroyed by fire, by Daniel Bethencourt and Katrease Stafford, Detroit Free Pres, 4 February, 2016. The rhetoric has spread internationally as well, as stories by The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, The Mirror and the International Business Times demonstrate.

2. Thomas Sugrue gives an account of this tumultuous period of extreme growth and discrimination in Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit.

3. Thomas Sugrue, in his analysis of deindustrialization Forget about Your Inalienable Right to Work describes many of these processes, especially those of automation.

4. What will come next?

_________________________________________________________________

Works Cited

Herron, Jerry. “Detroit: Disaster Deferred, Disaster in Progress.” South Atlantic Quarterly 106.4 (2007).

7.2 Sq Mi. “7.2 Sq Mi: A Report on Greater Downtown Detroit 2nd Edition.” The Hudson-Webber Foundation 2015.

Moore, Charles. “Augustus Brevoort Woodward: A Citizen of Two Cities.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington DC 4 (1901): 114-127.

Bluestone, Daniel M. “Detroit’s city beautiful and the problem of commerce.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 47.3 (1988): 245-262.

Detroit Future City. “Detroit Future City 2012 Detroit Strategic Framework Plan.” Inland Press. Detroit 2012.

Roberts, Arthur. “Paleo Indian on the North Shore of Lake Ontario.” Archaeology of Eastern North America (1984): 248-265.

Neavling, Steve. “’Bring on more gentrification,’ declares Detroit’s economic development czar.” Motor City Muckracker 16 May 2013.

_________________________________________________________________

Image Credits

Map Credit: Augustus Woodward, 1806. Source: detroit1701.org

All other maps, sketches and images are the work of this author.

Pingback: Recentering Detroit, Part 2: The French Connection |

Pingback: Recentering Detroit, Part 3: A Jeffersonian Digression |

Pingback: Recentering Detroit, Part 3: Infrastructure and Deeper Histor(ies) |

Interesting and excellent points though I feel it ignores that Metro Detroit is much more than Oakland verses Detroit. People feeling a connection to this greater community are stretched out to Ann Arbor and further west. They cross the Ohio border into Toledo. They cross the international boarder into Windsor. To look at 8 mile as the new center ignores so much more if who we are. Furthermore the impact of this metropolis goes up into the UP and west to Lake Michigan. Culturally and economical this state is “Detroit.”

To focus on 8 is similar to focusing on Southfield or Troy as city centers. The world does not view our city as such any more than they see Yonkers when they consider New York. They see Manhattan and its skyline. This defines our community core in the same way when it comes to competing globally for jobs, and we are competing globally (and because of the issues that you identify which have divided us, we have been loosing – jobs, pollination, and influence in DC).

I really appreciate your article and look forward to continued reading. I took away the following issues to confront:

Revitalization of an area considered a globally recognized center / engine of scientific (technological) progress while addressing issues that have defined and continue to define the community:

1) Industrial Age white racism against blacks by individuals, governments, unions, banks and systems. 2) Post Industrial Age automation, globalization, and government-subsidized suburban development.

3) Pre Industrial Age Detroit that came before the industrial city: a) Post-European Detroit with three centuries of history under the rule of three countries and b) as a region inhabited for 8,000 year with various Native Americans cultures.

I took note that you set up two points of view:

Restoring Detroit’s former grandeur, with a focus on the historic city center as our best chance to rebuild a tax base (Neavling).

Verses

Rejecting the assumption of centrality in downtown and focuses on the places where people live to rebuild (for lack of a better word at this moment) for the three million residents of the northern suburbs, and a good portion of the 700,000 residents of the city proper among 8 Mile Road as the true center of the region.

Thank you for this important conversation. I look forward to the next three parts.

Hello Steve! My apologies for taking (years) to reply to you. Around the time I published these posts I had to pick up a 2nd job, and was working 70 hours a week – and this project fell by the wayside. I hope you are well, and I thank you for your awesome, well thought out responses. Again, I’m sorry I wasn’t here to engage with you!